The Background: Conrad (not his real name), was notified that his grandmother died in Bremen, Germany. He flew over for the funeral, and talk naturally turned to the will. His mom, his aunts, and his uncle inherited the money, as was expected. However, Oma didn’t specify who would inherit her furniture and her art. None of it was worth much money, but it all had a lot of sentimental value.

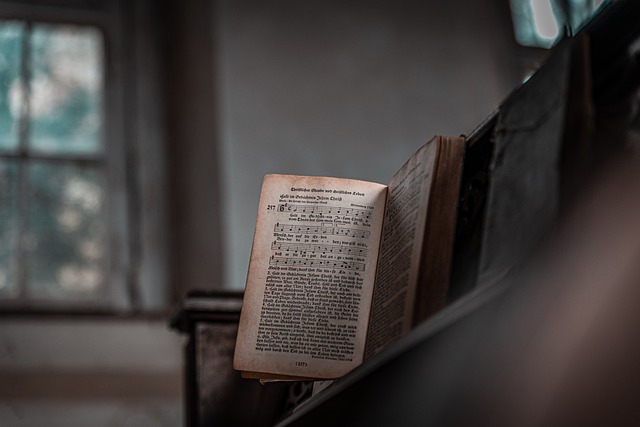

Conrad just wanted Oma’s piano. Not only was it Oma’s piano, she said it was her own mother’s childhood piano. She would tell him how it had survived a revolution, two world wars, the split and reunification. While Conrad had never met Uroma, he fond memories of visiting Oma throughout childhood and listening to her play in the parlor, everything from lullabies to classical, and sometimes, if she felt sassy she’d throw in the jazz and rockabilly she loved and learned to play as a young woman. That piano felt like true home to him. So when the family decided what they wanted from the estate, he chose the piano, and prepared to ship it to New York.

The Issue: There is an elephant ivory moratorium under CITES. You have to prove that an ivory item was made over a century ago, and that the item is not commercial trade. There are 55 white keys on a piano. Each key has two parts: the top and the face, making 110 pieces of ivory. Conrad knew the piano had ivory on it. He even filled out a CITES. But just filling out the paperwork doesn’t mean that you automatically clear the criteria. The road to losing your great-grandma’s piano is filled with good intentions.

The Outcome: Oma’s piano was stuck in limbo at the US Customs warehouse. Conrad paid for the packing, and a shipping container, and now was paying daily to warehouse it. Did he prove he had inherited it from his grandmother? No, since by German law, the money and real estate are all detailed in a will, but household items are not. He could be a shady antiques dealer who bought it at an estate sale and intended to sell it in the US. Were the ivory keys over 100 years old, because the piano belonged to his great-grandmother? Oma said so, and Conrad believed her, but maybe it was much newer, there was no way to tell.

At this point, get the piano back into his possession intact, Conrad would either have to ship it back to Germany, warehouse it there while he got it appraised and legally verified, then fill out the CITES and ship it back; or he could pay for a piano technician to go to the Customs warehouse with a Fish & Wildlife Agent, on their schedule, and have the technician pry off the ivory and surrender it to the Agent.

Conrad’s negligence was costing him a lot daily. Customs warehouses are different than regular warehouses. They have extensive security, and insurance. They are not cheap. As his budget went dry, he opted for the third, much sadder option. He stopped paying the warehouse fees, and eventually the keys were popped off with a screwdriver by a warehouse worker, and Oma’s beloved, now mangled piano was auctioned off to a stranger. He spent thousands of dollars, much of which was wasted in expensive warehousing, and in the end, lost the piano—priceless to him.

How we could have helped: Working with us, Conrad would have had a customized plan and checklist of the extra documentation needed to ship antique musical instruments that contain restricted animal elements, and given other options in good time to make informed decisions. Fish & Wildlife and US Customs is interested in making sure there is no profit in the trade of elephant ivory, not in owning Oma’s piano, or ruining Conrad’s memories. Conrad was hampered by his limited understanding of how to comply with CITES requirements. The piano would have arrived at the port, not just with the CITES permit, but with all the other documentation he needed, and then all Conrad would have needed was a couple of movers with a truck, and a piano tuner.